I have a note here from … gosh, it looks like last summer. And it pulls together a number of related points. Some of these are things I have griped about here before; others, probably not. But they are all related in an interesting way.

Much of the time, I have trouble understanding what I need.

My note starts by looking at my years in school. When I had to choose a topic to research, I'd always find something. But it was never a topic that anyone else cared about. It was never a topic that was going to take me somewhere. Let me explain what I mean by saying that.

In his book Post-Capitalist Society, Peter Drucker tells the following story:

The Hungarian-American Nobel prizewinner Albert Szent-Györgyi (1893-1990) revolutionized physiology. When asked to explain his achievements, he gave the credit to his teacher, an otherwise obscure professor at a provincial Hungarian university.

“When I got my doctorate,” Szent-Györgyi said, “I proposed to study flatulence—nothing was known about it and nothing is known about it still.”

“Very interesting,” the professor said, “but no one has ever died of flatulence. If you have results (and it’s a big ‘if’), you’d better have them where they’ll make a difference.”

“And so,” Szent-Györgyi went on, “I took up the study of basic bodily chemistry and discovered the enzymes.”

Every single one of Szent-Györgyi’s research projects was a small step. But from the beginning he aimed high: discovery of the basic chemistry of the human body.

That wasn't me. I would have ended up studying flatulence.

In practical terms, my bachelor's thesis was nearly the longest one ever submitted in my department (as of that time, at least), but from the perspective of research it was a dead end. I analyzed and explained some work that had been ground-breaking fifty years earlier. I did have one other topic in mind, but it involved studying someone that the whole department had written off as a crackpot. Sure sounded interesting, though.

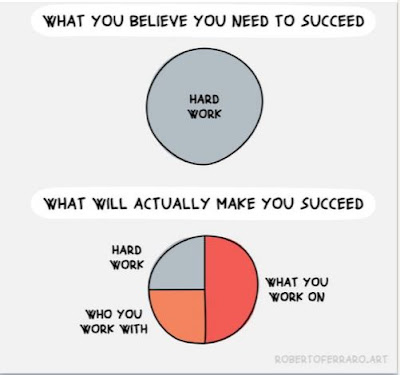

That's what I mean by saying that I have trouble understanding what I need. In an academic setting, some research topics make a difference when you get results. They carry you forward to the next thing. They grow and flourish. Others—that might seem, on the surface, just as interesting—don't. The truly successful researchers (and there are only a handful, generally) have a nose that lets them smell which topics are the right ones. Then they pursue those. The rest get bound in shallows and in miseries.

Back when I was in school, I didn't have such a nose. In retrospect, that's also why it was so hard for me to pick a major. I finally picked one, at the last minute and for the flimsiest of reasons. But I didn't have any special sense of smell leading me forward.

What about in other contexts? What about outside of school?

Well, I didn't have a very clear idea of what I needed in a romantic partner, so when I fell into a relationship with Wife I ended up marrying her. There were things I saw at the time that I didn't like, but I didn't know how heavily to weigh them because I didn't know what was most important. I didn't know what combination of features in a wife would help me achieve maximum personal growth and also maximum long-term happiness. (In the end I guess I got the growth. I surely missed the long-term happiness, at least as a by-product of marriage.)

In short, I didn't know what I needed.

And in my career, you've all heard me whine about not knowing what I really want to do when I grow up. (And I'd better hurry up to figure it out, because these days I'm over sixty.) But that's really the exact same issue, isn't it?

All these areas of my life—research, romance, and career—have been marked by indecision or bad decisions. And in all cases, it's because I haven't been able to understand what I really need.

It got to where I started to believe that indecision was a defining feature of my personality. And yet, in other contexts—contexts where I understood the framework and therefore could tell what was needed—I could make decisions with a certainty that bordered on arrogance. I might never have been convinced that I was in the right career; but when a professional problem came up in the context of that career I always knew exactly how to handle it. I had doubts about my marriage from the very beginning; but when some difficult parenting question came up, I learned to make a firm ruling right now and then apologize after if I really screwed up.

So it has never been that I can't decide. The problem has always been that I can't decide without a context, and that I have trouble understanding what I need (and therefore what the context is). It's a subtler point.

I'm not sure if that helps.

No comments:

Post a Comment